The Bachs were a remarkable family of musicians who were proud of their achievements. About 1735 Johann Sebastian Bach (the most famous member in our times) drafted a genealogy, in which he traced his ancestry back to his great-great-grandfather Veit Bach, a Lutheran baker (or miller) who late in the 16th century was driven from Hungary to Wechmar in Thuringia, a historic region of Germany, by religious persecution; he died in 1619. There were Bachs in the area before then, and it may be that, when Veit moved to Wechmar, he was returning to his birthplace. He used to take his cittern (an ancestor of the lute) to the mill and play it while the mill was grinding. Johann Sebastian remarked, “A pretty noise they must have made together! . . .This apparently was the beginning of music in our family.”

Many of the works of this Bach family were unknown to most musicians (or incorrectly attributed to others) until the rediscovery of the collection “Alt-Bachisches Archiv” from Johann Sebastian Bach’s music library. After Bach’s death, this was passed on to his second-oldest son, Carl Philipp Emanuel. The collection finally found its way into the possession of the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin, but was lost in the turmoil of the Second World War. After its spectacular rediscovery in Kiev (Ukraine) in 1999, the manuscript was returned to Berlin in 2001.

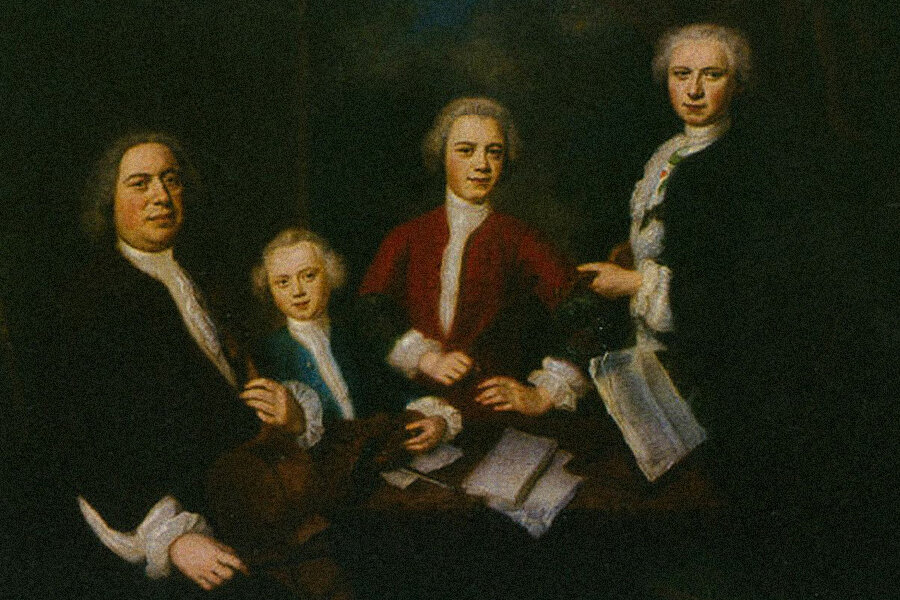

J.S. Bach and sons

Johann Bach (1604-1673), great uncle

Born in Erfurt, Johannes was the eldest son of Johannes Hans Bach. He was the father of the so-called "Erfurt line" of Bach family musicians. The family was so numerous and so eminent that in Erfurt musicians were known as "Bachs", even when there were no longer any members of the family in the town.

Unser Leben is ein Schatten

The motet is scored for eight parts, consisting of two choirs: the first choir is in five parts and the second, in three parts. In the opening, the composer uses musical gestures to underscore the text. The words “Unser Leben,” sung in a solemn low register, are effectively contrasted with “ist ein Schatten,” with rapid and fleeting rising lines on the word “Schatten.” Another instance of word painting is in the final chorale, where the last phrase “müssen alle davon” (must all vanish) is repeated several times and progressively accelerates, while at the end, all other voices hush and the sopranos sing “davon” one last time, before they, too, fall silent.

“For me there is hardly another musical work that conveys the ‘spirit’ of the Baroque–especially the era of the Thirty Years War, which was characterized by a sense of both transience and hope–as aesthetically and impressively as Unser Leben ist ein Schatten.” From the Carus choral music blog.

Johann Christoph Bach (1642-1703), uncle

Within the Bach family Johann Christoph was highly respected as a composer (a “profound'” one, according to the Ursprung[ST1] ). In J.S. Bach's writings, he is mentioned expressly as one who “was as good at inventing beautiful thoughts as he was at expressing words. He composed, to the extent that current taste permitted, in a galant and cantabile style.”

Herr, nun lässest du deinen Diener

This is a graceful and simple setting of the famous Song of Simeon (Nunc dimittis), from the St. Luke Gospel. The text is enhanced by beautiful and elegant rhythmic gestures.

Es ist nun auf mit meinem Leben

This motet is a setting of four of the six verses of the chorale; the harmonization is simple, and yet the rising line in the soprano part near the end of each verse adds a lyrical dimension. The text is given all of the attention here, and the challenge is to make each verse (otherwise in an identical musical setting) convey its particular message. The overall theme of the motet is a sweet acceptance of death.

Lieber Herr Gott, wecke uns auf

Apparently, Johann Sebastian Bach arranged an instrumental accompaniment to this motet a few months before his death in 1750 and possibly also asked for it to be performed for his funeral. Christoph Wolff, said, "It is an extraordinarily expressive piece that gives us an insight into Bach's funeral, about which we basically knew next to nothing beyond that Bach was put in an oak casket and given a free hearse."

Johann Ludwig Bach (1677-1731), distant cousin

Johann Ludwig Bach was born in Thal near Eisenach. He was a third cousin of Johann Sebastian Bach, who made copies of several of Johann Ludwig’s cantatas and performed them at Leipzig.

Unsere Trübsal die zeitlich und leicht ist

The motets of Johann Ludwig Bach are rooted firmly in the shorter motets from the Thuringian tradition, but as a court composer he was exposed to other styles and incorporated them as well. Varying ensembles and dialogue-like passages contribute to these richly expressive compositions. In this motet, for example, the composer employs various configurations of the high, middle, and low voices to add color to the words. The mournful first section on life’s tribulations yields to a joyful section in triple meter, expressing anticipation and hope, and a concluding section of vigorous rhythms, contrasting the “seen” and “unseen” glories to come after suffering ceases.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

This composer barely needs an introduction, as the most well known, thoroughly researched, and most performed member of this family. However, as we see from the family history, he comes from a long line of distinguished musicians.

Johann Sebastian Bach

For about fifty years after Bach’s death, his music was neglected. This was only natural; in the days of Haydn and Mozart, no one took much interest in a composer who had been considered old-fashioned even in his lifetime. Yet, his music never went out of circulation entirely, at least among sophisticated musical circles, and broader general interest in his works was revived by such nineteenth century composers as Mendelssohn and Schumann. In retrospect, the Bach revival, reaching back to 1800, can be recognized as the first example of the deliberate exhumation of old music, accompanied by biographical and critical studies. The revival also served as an inspiration and a model for subsequent work of a similar kind.

Jesu, meine Freude

This motet is one of the few works by Bach for five vocal parts. Christoph Wolff suggested that the motet may have been composed for education in both choral singing and theology. Unique in its complex symmetrical structure juxtaposing hymn text and Bible text, the motet has been regarded as one of Bach's greatest achievements in the genre.

As a key teaching of the Lutheran faith, the Bible text reflects on the contrast of living "in the flesh" or "according to the Spirit." The hymn text was written by the theologian Johann Franck, from an individual believer's point of view, that addresses Jesus as joy and support, against enemies and the vanity of existence, which are expressed in stark images. The hymn adds a layer of individuality and emotions to the Biblical teaching.

The music is arranged in different layers of symmetry around the sixth movement. The first and last movements have the same four-part setting of two different hymn stanzas. The second and next to last movements use the same themes in fugal writing. The third and fifth movements, both five-part, mirror the seventh and ninth movements, both four-part. The fourth and eighth movements are both trios: the fourth for the three highest voices; the eighth for the three lowest voices. The central movement is a five-part fugue. The six hymn stanzas form the odd movement numbers, while the even numbers each take one verse from the Epistle as their text.

Ich lasse dich nicht

This SATB double choir motet was attributed to Johann Sebastian Bach when it was first published in 1802. Around 1823 the motet was published as a composition by Johann Christoph Bach, after which its attribution became a matter of discussion among scholars.

The text of its first movement consists of a quote from Genesis 32:27 and the third stanza of the Lutheran hymn "Warum betrübst du dich, mein Herz." Such a mixture of scripture and chorale texts was common for motets of the generation before Johann Sebastian, as was its eight-part setting. Over-all the complexity and style of this movement's setting appears closer to similar works by a young Johann Sebastian than to works by a mature Johann Christoph.

Bach Family: (From Left) Johann Sebastian, Carl Phillipp Emanuel, Johann Christian, Wilhelm Friedemann, Johann Christoph Friedemann

Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach (1732-1795), son

Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach was a son of J. S. Bach and his second wife, Anna Magdalena. He pursued a fusion of the counterpoint he had learned with "the simpler textures and harmonies of the South," namely, the Italian style.

Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme

This is a chorale motet composed around 1780. It is based on Philipp Nicolai's hymn by the same name.

The motet is written for a four-part choir. It is structured in three movements, corresponding to the three stanzas of the hymn. The first movement is an extended chorale fantasia; the second develops motifs from the first movement; the third includes a quotation of his fathers's closing chorale from his cantata Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 140.

The musicologist S. Lachtermann notes: "The shape of the lines, and the contour of the harmonic progression are 'modern,' but the interlacing of voices and the focus on individual words harken back to his father’s art."

Sources: Wikipedia, Carus Music blog, Professor Christoph Wolff (Harvard University), Encyclopedia Brittanica

Patricia Jennerjohn, September 2021